By Max Cane, Rensselaer Class of 2010, president and COO of ProTek Recycling.

I clearly remember the day I was led into a trendy midtown office right off 6th Ave, right into a multimillion-dollar conference room piled high with electronics—everything from old switches to LCD televisions. The company had a meeting in there later that day so the employee who had contacted me was really hoping we could take everything in that room, and two others.

We left that day with two 16-foot box trucks full of electronics, and a business that was budding before my eyes. It was clear that there was a significant demand for electronics recycling, but at the same time I found it odd that there wasn’t a more centralized process for it already in place.

Electronics recycling isn’t new. Recovering valuable commodity material or spare parts from outdated computer systems has been going on since the days of mainframes. But it’s only relatively recently that the environmental impact of improperly discarded systems has entered the public’s awareness.

Harrowing images of people in Third World nations sifting through veritable mountains of TVs and computer cases is unfortunately what most people associate with the term “e-waste.” And while this type of discarding does occur on a large scale, it always struck me as counterintuitive since the material and components do have value to them.

I started ProTek Recycling toward the Spring of 2012 when I was still a student at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. With help from my mentor, we created a business plan and hired our first employee, Chris Fuller, another student at RPI. He is now our COO. Together we set about designing an electronics recycling company from the ground up.

Part of what’s so challenging about electronics recycling is the inherent complexity. So many different types of equipment are all lumped together under the umbrella of e-waste, but each one has to be handled in a largely separate process.

Desktop computers have some components in common with laptops like RAM and processors, but you can’t break them down in the same fashion and they end up having very different residual markets. Televisions need to be sorted by their different technologies and recycled in a different manner, each with their own individual challenges.

Equipment like printers are fairly benign with almost no hazardous elements, while battery backups are built with (sealed) lead-acid batteries that can be extremely dangerous.

The saving grace with this industry is that absolutely everything, including the hazardous elements, can be recycled and reused. Lead from lead-acid batteries, for example, is readily purchased by battery manufacturers since it’s much more economical to remanufacture the batteries than to start from scratch with mined material.

Economic upsides like this drive the recycling business behind the scenes and refineries have been constructed to handle almost every type of material used in electronics. Some may take in hundreds to thousands of tons of electronic parts per year and convert it all into refined material destined for manufacturing.

The challenge for recycling companies like ours is separating the different types of materials and accumulating enough so that it’s worth it for the refineries to work with us. A perfect example is motherboards which, like other circuit boards, contain a high concentration of valuable commodity materials like gold, silver, copper, palladium, and tantalum.

Unfortunately, a processing batch size for these refineries is typically 50,000 pounds. Since the average computer motherboard is 1 to 2 pounds, it would be impractical for us to accumulate that much ourselves, so intermediary companies purchase boards from us, sort them by grade, and accumulate batches for the refinery. Similar processes exist for other materials and that allows us to keep cash flow steady and focus on our real area of expertise—reuse.

Most electronics recyclers came from the waste management industry and tend to focus on logistics and commodity materials. Chris and I came from a more technical background—my undergraduate degree was in chemical engineering and my masters was in geology, Chris’ master’s degree was in industrial and management engineering—so we approached e-waste from a different angle.

Much of what is discarded, especially by larger companies, may still be working or have modest issues like a bad hard drive or cosmetic damage. By taking working parts from these systems, or even refurbishing them fully, we can put together a computer system that can then be resold for use. We price these systems far below what a new computer would cost, which allows small businesses and students access to equipment they might not otherwise be able to afford.

By focusing on refurbishment and reuse, in most cases we can offer the recycling to companies in New York City and Boston at no cost. Our only caveat is that the quantity to recycle has to be large enough to keep the logistics economical—a minimum of 20 to 30 computers.

Keeping the recycling free is an important aspect of our model because it encourages companies to keep the equipment out of the landfill. While I do find that many people have an ideological desire to recycle properly, the no-cost benefit is what can tip the scales.

Our main challenge seems to be getting the word out that there is a service like ours. To date we’ve picked up from over 1,000 different companies, schools, and nonprofit organizations in the New York City area. And while that number seems enormous, we’ve only begun to scratch the surface as to how much is out there waiting to be recycled.

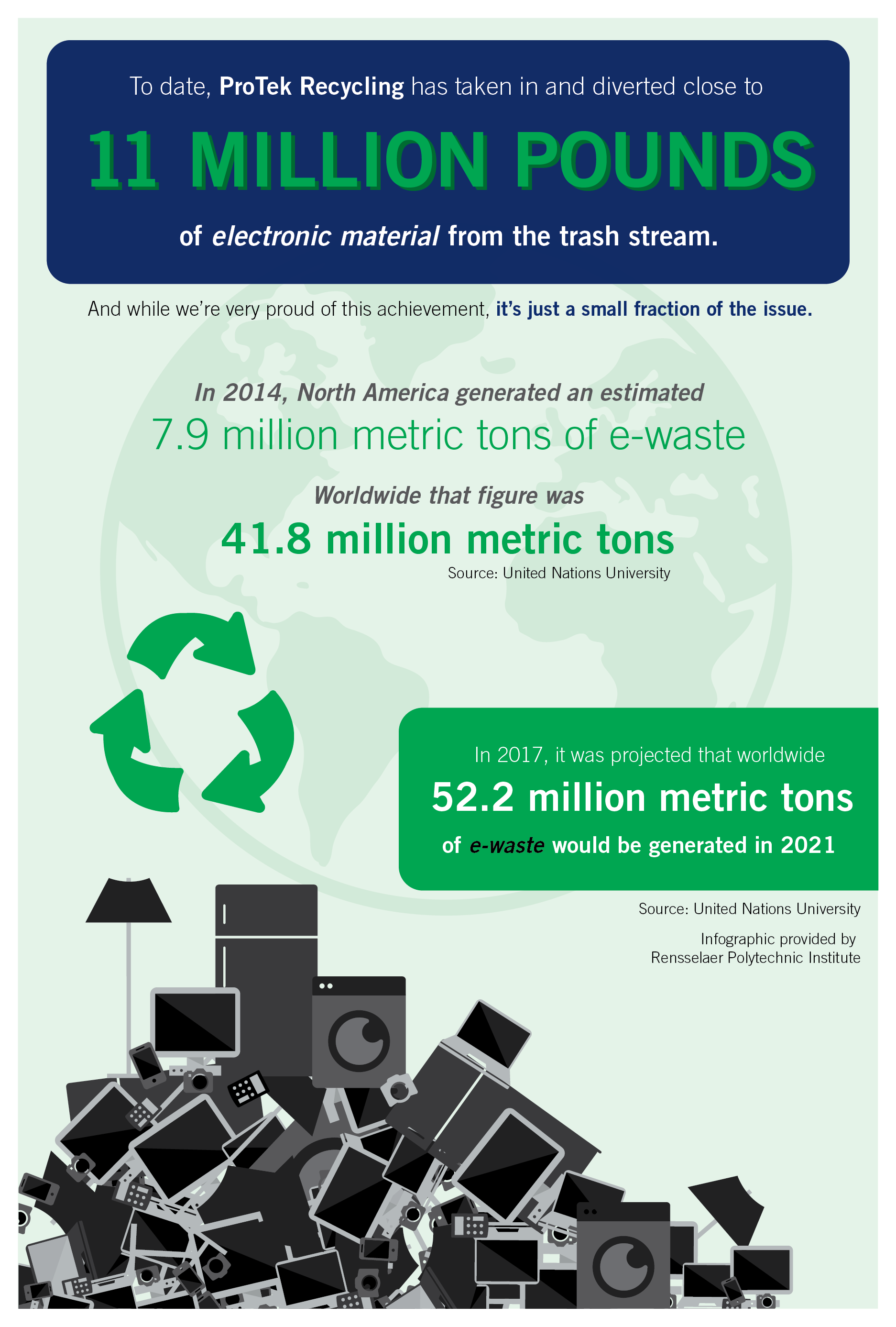

To date, ProTek Recycling has taken in and diverted close to 11 million pounds of electronic material from the trash stream. A few times we’ve hit 2 million pounds in a single year. And while we’re very proud of this achievement, it’s just a small fraction of the issue.

According to a United Nations University report in 2014, North America generated an estimated 7.9 million metric tons of e-waste. Worldwide that figure was 41.8 million metric tons.

United Nations University released another report in 2016, estimating 44.7 million metric tons of e-waste were generated that year nationwide. Only 20% of that is documented to have been recycled properly. That report also projected 52.2 million metric tons of e-waste would be generated in 2021.

That’s still quite a gap and there’s no quick way to close it. Worldwide production grows each year but so does the recycling industry and the capacity for processing the material. Consumer sentiment will be the key.

Individual people saving and bringing their electronic waste to recycling events or collection points and pushing their companies to enact e-waste recycling programs will be what tips the scales. And while it may be awhile until those mountains of e-waste are a distant memory, the technology and processes already exist to make that happen.