“We are seeing very good quality data from this detector, which tells us that it is running perfectly,” said Ethan Brown, a XENON1T Collaboration member, and assistant professor of physics, applied physics, and astronomy.

Dark matter is theorized as one of the basic constituents of the universe, five times more abundant than ordinary matter. But because it cannot be seen and seldom interacts with ordinary matter, its existence has never been confirmed. Several astronomical measurements have corroborated the existence of dark matter, leading to a worldwide effort to directly observe dark matter particle interactions with ordinary matter. Up to the present, the interactions have proven so feeble that they have escaped direct detection, forcing scientists to build ever-more-sensitive detectors.

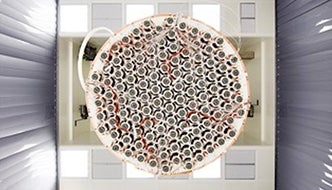

Since 2006, the XENON Collaboration has operated three successively more sensitive liquid xenon detectors in the Gran Sasso Underground Laboratory (LNGS) in Italy, and XENON1T is its most powerful venture to date and the largest detector of its type ever built. Particle interactions in liquid xenon create tiny flashes of light, and the detector is intended to capture the flash from the rare occasion in which a dark matter particle collides with a xenon nucleus.

But other interactions are far more common. To shield the detector as much as possible from natural radioactivity in the cavern, the detector (a so-called Liquid Xenon Time Projection Chamber) sits within a cryostat submersed in a tank of water. A mountain above the underground laboratory further shields the detector from cosmic rays. Even with shielding from the outside world, contaminants seep into the xenon from the materials used in the detector. Among his contributions, Brown is responsible for a purification system that continually scrubs the xenon in the detector.

“If the xenon is dirty, we won’t see the signal from a collision with dark matter,” Brown said. “Keeping the xenon clean is one of the major challenges of this experiment, and my work involves developing new techniques and new technologies to keep pace with that challenge.”

Brown also aids in calibrating the detector to ensure that interactions that are recorded can be properly identified. In rare cases, for example, the signal from a gamma ray may approach the expected signal of a dark matter particle, and proper calibration helps to rule out similar false positive signals.

In the paper “First Dark Matter Search Results from the XENON1T Experiment” posted on arXiv.org and submitted for publication, the collaboration presented results of a 34-day run of XENON1T from November 2016 to January 2017. While the results did not detect dark matter particles—known as “weakly interacting massive particles” or “WIMPs” —the combination of record low radioactivity levels with the size of the detector implies an excellent discovery potential in the years to come.

“A new phase in the race to detect dark matter with ultralow background massive detectors on Earth has just began with XENON1T,” said Elena Aprile, a professor at Columbia University and project spokesperson. “We are proud to be at the forefront of the race with this amazing detector, the first of its kind.”

The XENON Collaboration consists of 135 researchers from the U.S., Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Portugal, France, the Netherlands, Israel, Sweden, and the United Arab Emirates.