By Richard Jurek

George M. Low, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Class of 1948, was an early and indispensable pioneer in the nation’s fledgling space program. Long considered NASA’s ultimate engineer, he was one of the leading advocates for a lunar landing program. Yet for most people outside of NASA and RPI, his story remains a mystery, hidden in the long and dominant shadows of NASA media giants such as Wernher Von Braun and the dynamic personalities of the moonwalkers themselves.

For his part, Low was never one to seek out the limelight, or to try and garner credit for himself. But the fact of the matter remains: He was elemental in achieving Apollo 11’s landing in 1969.

Indeed, Low’s boss, and NASA Administrator James Fletcher, underscored this notion when he wrote: “Without George Low in exactly the places he occupied at NASA, the United States would not have been able to land men successfully on the Moon.”

Tall, calm, and unassuming, Low had a lifelong affinity for working on all things mechanical. A self-described “dirty-hands engineer,” he once said that he wanted to be an engineer before he even knew what it meant to be one.

He learned to be an aeronautic engineer studying under Paul E. Hemke, founder of RPI’s aeronautical and metallurgical engineering program, and by experimenting in the basement of the Ricketts Building in the department’s first wind tunnels and engine testing lab. “Whatever I accomplished at NASA or contributed to the space program, really began right here at RPI,” Low said.

Low went to Washington when NASA was formed in 1958 to be the agency’s first chief of manned space flight. In this role, he not only helped design, fund, and manage what would become the Mercury program, he was also responsible for some of the boldest decisions in NASA’s history, including introducing the world to the Apollo program when it was still on the drawing board, as well as being its principal advocate behind the scenes in Washington.

In April 1959, as a member of the so-called Goett Committee charged with producing a long-range strategic plan for NASA, it was Low who provided an unwavering and powerful voice pushing for a lunar landing. He was such a passionate advocate that one journalist even went so far as to call him “the original Moon zealot.”

Unlike other early NASA figures, Low wasn’t inspired by childhood dreams of flying rockets into space. Rather, it was the dirty-hands engineer in him that viewed a moon landing as a technically challenging—and, therefore, worthy—strategic goal for the expense and risk, one that would advance the country’s industrial and technology base the furthest.

“Without risk, there can be no progress,” Low often said. But he also believed that the risks needed to be balanced with the rewards. He went out of his way to promote a feasible program that would accomplish this delicate balance.

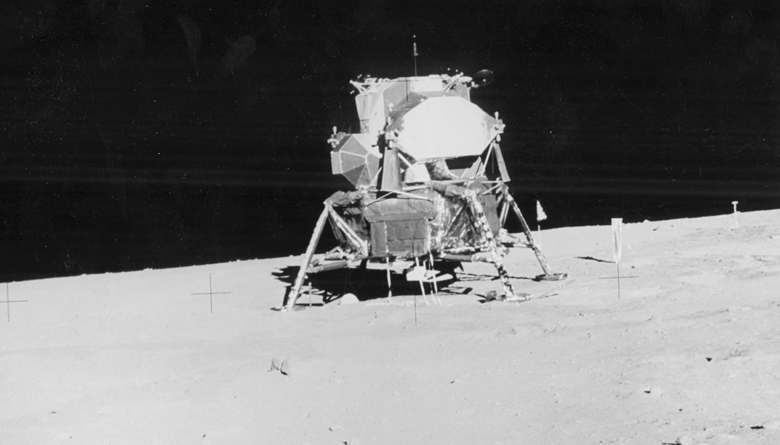

In early 1961, Low wrote the NASA report that President John F. Kennedy based his decision on to formally commit NASA to the goal of landing a man on the moon. In many ways, when Neil Armstrong set foot on the lunar surface on July 20, 1969, he was not only fulfilling Kennedy’s stated goal, but he was also realizing the engineering and technological challenge that Low had proposed for the nation 10 years earlier.

In January of 1967, the disastrous Apollo 1 fire killed three astronauts and put the whole program’s future in doubt. In this tragic moment, NASA turned to Low for leadership and inspiration. He was charged with redesigning the spacecraft and getting Apollo back on track to land a man on the moon by the end of the decade. Astronauts like Armstrong regained complete faith in the equipment and vehicles they used mostly because of Low’s expert project management and engineering work. He was a natural born leader, and he was the right man to save the program when it needed his skills the most.

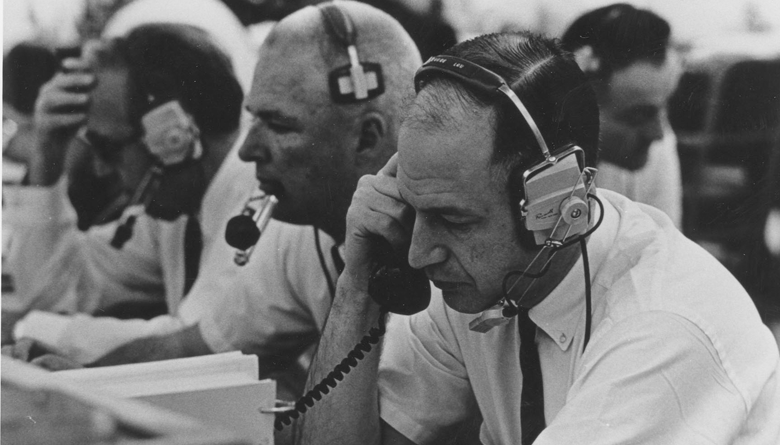

In fact, all of Low’s colleagues at the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston had great faith in his leadership. “George Low was a master at getting people to work together,” recalled flight director Gene Kranz. “You would do whatever he asked you to do, regardless of the odds and regardless of the risks,” said Kranz. “And you did so because you knew he sweated the smallest, most minute detail.”

“Spaceflight is unforgiving,” Low wrote in a New York Times article, published the day after Apollo 11 successfully lifted off for the moon. “We once made a serious mistake (on Apollo 1) of not maintaining absolute control over all flammable material, and it took the lives of three of the finest men I have ever known.” In the article, Low emphasized the engineering and project management principles that he employed to put the program back on track: asking the right questions, maintaining control over all engineering changes, paying excruciating attention to detail, having a robust testing regime, and making sound technical judgements.

Of these, according to Low, none were more important than paying attention to detail and learning to ask the right questions.

“No engineering change is insignificant,” he said. “A change that may, in a subsystem-engineer’s mind appear to be an improvement, might well degrade a system’s overall reliability. We know, from long experience, that attention to every detail, no matter how small, is mandatory.”

In a campus speech he gave in 1975, shortly before becoming RPI’s 14th president, Low addressed some of the important skills he learned as a student that helped him to land a man on the moon in 1969. “I learned how to be inquisitive,” he said. “I learned to be curious. I learned not to be afraid to ask questions. Once a question is asked, once a problem is identified, a solution can always be found. In space, we are successful because we are curious, because we look for answers. And whenever we did have a failure, the reason was always the same: We had failed to be inquisitive.”

Low always kept this fundamental principle in mind. It was a foundational truth for him as an engineer. He knew that lives depended on the thoroughness and completeness of his work. He believed that any failure was predicated on not asking the right questions at the right time.

“I think the kind of question one has to ask, the motivation one has to have, and every decision one has to make has to be based on the knowledge that one day you will have to tell the person who is going to fly the machine: ‘I’ve done the best job I know how to do for you,’ ” Low said. “I put myself ahead—in time, not space—and say, ‘If I make that decision in this way today, how will I feel at midnight in the Mission Control Center during the flight if something goes wrong?” During all the Apollo flights, Low made it a habit to have breakfast with the astronauts the morning before a launch. He wanted to shake their hands, look them in the eye, and let them know he had done everything he could to keep them safe.

“From June 1967 to July 1969, we tore the command module apart—literally all 2 million parts—and then we put it back together the way we wanted it to be,” Low said, explaining the amount of work needed to whip the spaceship into shape. As Low rebuilt the Apollo spacecraft, his ever-probing questions drove the process.

“In the astronaut corps, we marveled at the new Apollo spacecraft taking shape,” astronaut Alan Shepard confirmed. “We were gaining confidence all the while that, yes, they’re creating something that will be safe for us to fly.” And something that would get them to the moon and back not only during the historic flight of Apollo 11, but on all of the Apollo program flights.

While over 400,000 people worked on Apollo at its peak, Low’s singular contributions stand out among the rest. “As usual with any great endeavor, it always boils down to a single human being who makes a difference,” Apollo 8 commander Frank Borman said, underscoring this point. “In the case of Apollo, the person in my mind who made the difference was George Low.”

And it seems that Apollo 11 Commander Armstrong would have agreed with Borman. At the 50th anniversary of NASA Glenn in Cleveland, where Low went to work for the first time after receiving his master’s degree from RPI, Mark Low (RPI ’78), his son, was re-introduced to Armstrong. Both George Low and Armstrong had worked together briefly at the facility in the late 1950s.

Upon hearing Low’s name, he gave Mark a pleasant, reassuring smile, and shook his hand. As someone himself who only wanted to be known for his engineering skills, and not only for his one “giant leap” in 1969, Armstrong immediately paid George Low’s memory the ultimate compliment: “He was my favorite engineer,” the first man declared.

Richard Jurek is a contributor to the Smithsonian’s Air & Space magazine and website. He is co-author of the best-selling book “Marketing the Moon: The Selling of the Apollo Lunar Program,” and he served as a consulting producer on the award-winning PBS/American Experience documentary “Chasing the Moon.” His is the author of “The Ultimate Engineer: The Remarkable Life of NASA’s Legendary Leader George M. Low,” which will be published later this year by the University of Nebraska Press.

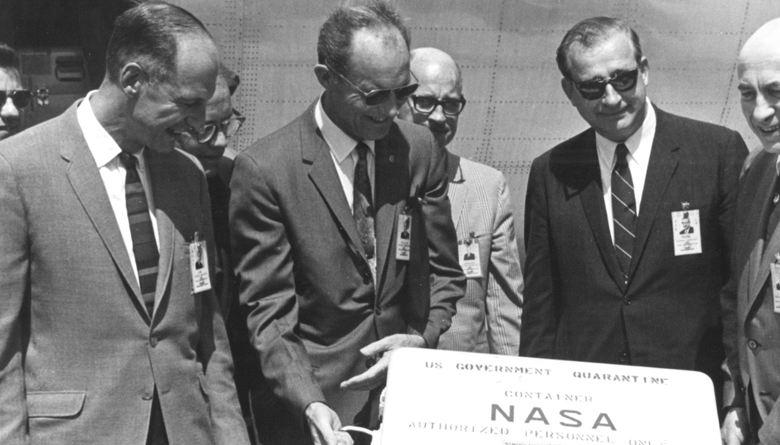

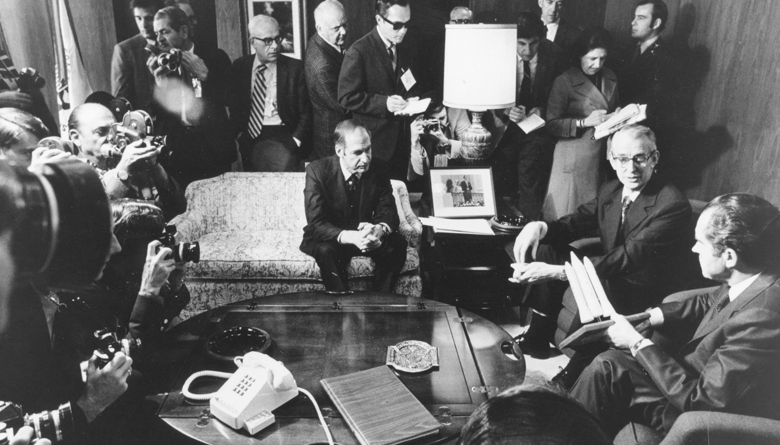

Images courtesy of NASA and RPI Archives