Team TROOPER will take on contenders from around the globe—and tackle some of the most daunting disaster response tests—during the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Robotics Challenge finals June 5-6 in Pomona, California. The team is a partnership of Rensselaer, Lockheed Martin, and the University of Pennsylvania.

One of the world’s most difficult robotics competitions, the challenge requires humanoid robots to drive to a simulated disaster zone, exit the vehicle without assistance, and complete a circuit of complicated physical tasks. The goal is to improve disaster response by developing semi-autonomous robots that could be dispatched to areas too dangerous for humans.

The winning team will receive $2 million. The second-place team will win $1 million, and the third-place team, $500,000.

Team TROOPER is one of 11 to qualify for the finals by placing among the top finishers in previous contests. Another 14 teams qualified by submitting videos of their robots in action. Together, the 25 finalists represent the U.S., China, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, and South Korea.

Team TROOPER is one of 11 to qualify for the finals by placing among the top finishers in previous contests. Another 14 teams qualified by submitting videos of their robots in action. Together, the 25 finalists represent the U.S., China, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, and South Korea.

The finals feature some challenges that contestants have seen before. Robots will be expected to drive, enter and exit a building, climb ladders, close valves, and drill a hole in the wall. However, for the first time:

· Robots will be untethered. With no power cords, fall arrestors, or wires, robots will operate on battery packs and have to recover from falls unassisted. Teams will rely on wireless communications.

· Tasks will have to be completed in order, in an hour or less—and will include a surprise that teams have not been able to prepare for in advance.

· Communications will be degraded and intermittent, forcing robots to make some decisions without their human teammates.

“The DARPA Robotics Challenge was designed to push the teams and their robots to perform beyond what was thought to be nearly impossible just a few years ago,” said Jeff Trinkle, professor of computer science and director of the Rensselaer Computer Science Department Robotics Lab. “The challenge has accelerated progress, and the finals competition will set performance standards for future robots to exceed.”

Trinkle is on leave from Rensselaer while serving as a program director for the Division of Information and Intelligent Systems of the National Science Foundation, responsible for the National Robotics Initiative. He remains a member of Team TROOPER, along with Rensselaer doctoral student Jun Dong and post-doctoral researcher and visiting scholar Daniel Montrallo Flickinger.

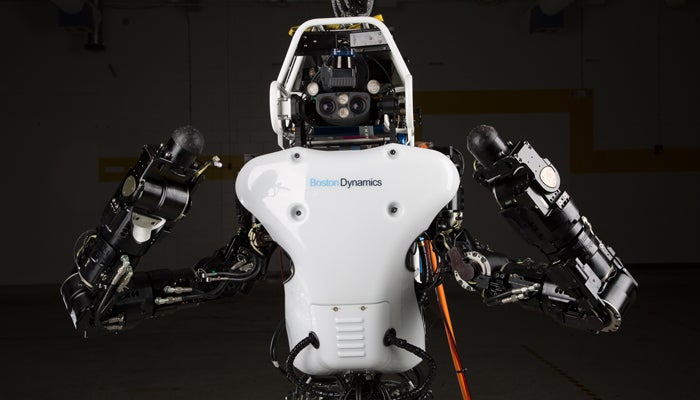

Most of the teams have designed their own robots and software. Seven, including TROOPER, are writing software for the Atlas humanoid, which was developed for DARPA by Boston Dynamics. The robot was redesigned for the finals and is stronger, more energy efficient, and has more dexterity than its predecessor.

The upgraded, cordless Atlas stands 6 feet 2 inches tall, weighs 345 pounds, and is equipped with a battery, pressure pump, wireless router for communication, and three computers for perception and task planning. Arms have been repositioned so Atlas can better sense what its hands are doing. Redesigned wrists enable Atlas to turn door handles simply by rotating its wrist, instead of its entire arm.

Lockheed Martin plays the lead role on team TROOPER and is responsible for the overall software structure and communication. Rensselaer team members focus on upper body planning and manipulation. University of Pennsylvania team members work on perception and lower and whole body control for walking and balancing tasks. “Together, we form an amazing team,” Dong said.

Since much of their work is done remotely, in simulation, Dong and Flickinger have not yet seen the latest version of Atlas. But both are impressed with the upgrades and the resulting opportunities for increased autonomy. “That will be especially important during the finals, when communications between the operator and robot are degraded,” Flickinger said.

Dong agrees, citing the emphasis on autonomy as a key difference between the DARPA trials in December 2013 and the finals in June. “During the trials, many of the operators relied on remote control,” Dong said. “They would see what the robot perceived and then use remote control to guide the robot’s arm.”

For the finals, Dong is developing software to help the robot execute pre-set trajectories for specific tasks and objects in an unknown environment. The goal is for the robot to find a good standing pose, match pre-set trajectories, and perform the required task. Dong and Flickinger look forward to attending the finals and expect another strong showing for Team TROOPER.

Regardless of the outcome, “the DARPA Challenge will show the enormous progress made by the robotics research and development community,” Trinkle said. “At the same time, it will demonstrate that some important, tough problems remain unsolved.”