Most people see food and clothing as distinct entities that help support human life. Nancy Diniz, assistant professor of architecture at the Rensselaer Center for Architecture, Science, and Ecology (CASE), views them as intertwined. Recently, she and three summer research students applied her boundary-defying research to building a prize-winning prototype of a product that can be worn, slept in, and eaten.

The item, a waterproof jacket built from a fungus found in mushrooms, earned Diniz and the students honorable mention in a competition sponsored by the progressive group Social Cooperation Architects. As a result, posters of the jacket built by Diniz and students Boqun Huai, Anqi Huo, and Alexandria Frisbie are now exhibited at the Milano Expo 2015.

Running from May 1 to October 31, the Expo is a highly influential platform for addressing the world’s broad questions. The theme this year, “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life,” examines the tragic paradox of world hunger and food waste. The Expo’s exhibits and events look at how to achieve a balance between the availability and consumption of resources. Social Cooperation Architects (known as SCoopA) incorporated the theme in its “Solutions” competition, inviting architects, designers, engineers, and artists to submit proposals for creating change and awarding winners an opportunity to display their work at the Expo. The challenge was perfectly suited to Diniz, an architect who teaches Materials Systems and Productions at CASE and with Rensselaer’s Geofutures graduate program. Her research and teaching interests question boundaries between design disciplines—fashion, product, computer science, and architecture. With an eye toward minimizing the impact on the environment, she, together with colleagues and Ph.D. students at CASE, is developing processes to put biomaterials to multiple uses.

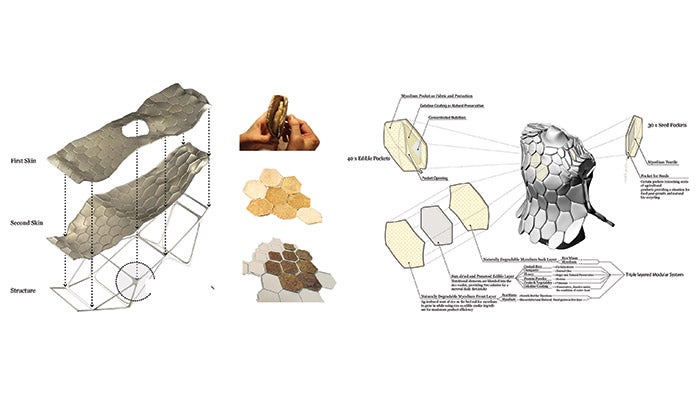

For the SCoopA competition, she and the students devised the “MUSHRICE Series,” which grows a waterproof material from mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungi, mixed with latex in a tessellated textile. Over just two weeks, they designed and prototyped what can best be described as a poncho that can be worn, used as a blanket, and then eaten. They did so by baking the mycelium of mushrooms to grow a durable textile.

Diniz notes that exploring biomaterials is an important area of research at CASE. In addition to mushrooms, she has worked with corn and flax and has collaborated with Ecovative Design, the company started by Rensselaer students who developed an insulation using mushrooms. Diniz wanted to apply the process to creating a textile.

“Inspired by the topic of the competition, I wanted to play with the idea of wearing, sitting on, and eating one material,” says Diniz, who joined the Rensselaer faculty in January. “In my research I focus on multi-scalar materials that one can use as garment and product design, but which can sense both the environment and the body. Eventually we can prototype it as an architectural surface, too.”

She sees her role as working across the disciplines and influencing her students to advance uses of biomaterials. Net barriers today include the cost and time the process requires.

“Growing materials is a very beautiful and fascinating process and I believe it is an important skill for future designers to develop,” she notes. “One of the reasons materials are not manufactured in greater scale is that the manufacturing process is so complicated, at least at the moment.”