A new study led by engineers at Rensselaer demonstrates, for the first time, a simple method for determining the strength and stiffness of practical samples of the nanomaterial graphene.

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, includes data that enables researchers to correlate the precise strength and stiffness of non-pristine graphene samples to their Raman signatures. Raman spectroscopy is a simple, non-contact, and non-destructive method widely used by scientists and engineers to characterize the state of defectiveness of graphene.

This fundamental research finding holds the potential to help inform the development and creation of new composite materials, nanoelectronics, and devices that take advantage of graphene’s unique mechanical properties.

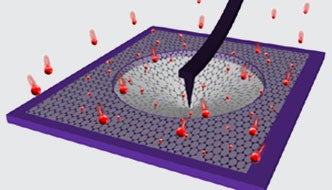

The researchers used a nano indentation technique to press sharp diamond tips into the graphene samples, and recorded how the samples stretched and tore.

“Our results provide researchers a facile, rapid, and non-destructive method to determine the strength and stiffness of graphene samples, with a high degree of accuracy,” said Nikhil Koratkar, the John A. Clark and Edward T. Crossan Professor of Engineering, who led the study. “This data will be immediately useful to everyone in academia, government, and industry who uses graphene in their research and product development.”

The thinnest material known to science, graphene is a single layer of carbon atoms arranged like a nanoscale chicken-wire fence. Graphene is physically strong and chemically inert; researchers have been investigating how to leverage its properties to develop applications including batteries, gas sensors, and computer chips.

A landmark study published in 2008 characterized the strength of a pristine layer of graphene that was isolated by using common adhesive tape to exfoliate a layer of graphene from bulk graphite (like the graphite commonly found in pencils). This method of creating graphene, however, is prohibitively time-consuming and not suitable for producing large quantities.

Other processes used to create large quantities of graphene, including chemical vapor deposition and oxidizing graphite, result in graphene layers with holes, voids, leftover oxygen atoms, and other defects. In this new study, Koratkar and the research team investigated how the density and type of these defects affect the mechanical properties of such practical graphene samples that are most commonly used in laboratories.

The research team created samples of graphene with a range of densities and types of defects, and then characterized the samples using Raman spectroscopy. The team then used a nanoindentation technique to press sharp diamond tips into the graphene samples, and recorded how the samples stretched and, in some cases, tore.

Koratkar said he was surprised by the finding that graphene is able to retain its outstanding mechanical properties even after its surface is littered with oxygen atoms, which disrupt the graphene’s perfect sp2 carbon bonding network. This is interesting, he said, since the electrical and thermal properties of graphene are known to degrade significantly due to such defects, but this study indicates that graphene sheets are far more rugged and mechanically robust than what was previously thought.The study also indicated that when holes or vacancy defects are created in the graphene structure, its strength and stiffness degrades significantly.

An important practical implication of this work is that it provides a direct relationship between the intrinsic strength and stiffness of defective graphene samples and their Raman signature.