By Torie Wells

Brown cardboard boxes. Packing tape. Delivery trucks. They’ve become so commonplace in a society where books, clothes, and even food can be delivered to your door in a matter of days—sometimes hours.

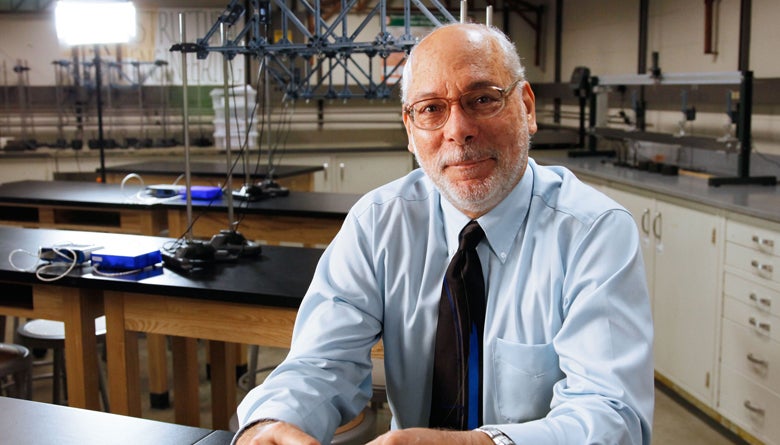

José Holguín-Veras, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, spends much of his time thinking about the effect that delivery explosion has on city streets, the environment, and businesses across the country and the world.

“The number of freight trips in New York City is larger than the number of deliveries when New York City was a manufacturing powerhouse in the 1960s,” said Holguín-Veras, who is also the director of the Volvo Research and Educational Foundations (VREF) Center of Excellence for Sustainable Urban Freight Systems.

He said that developing new, business-friendly sustainable solutions for shipping goods is an increasingly pressing concern.

“Because of the gravity of climate change, we need to use collaborative approaches involving the public and private sectors and researchers to find solutions not only to benefit the environment, but also to increase economic productivity,” he said.

Holguín-Veras’ research has found that relatively small changes in the timing and frequency of freight deliveries—such as switching the standard delivery window from day to night—may have significant environmental and economic advantages.

A key example is the Off-Hour Delivery program designed by Holguín-Veras and his team, which was implemented in New York City. Data his team collected and analyzed showed a considerable benefit to commuters, businesses, and the environment when deliveries were made and accepted between the hours of 7 p.m. and 6 a.m.

This shift in scheduling is effective because trucks that are traveling on less congested roadways can take more direct routes, cutting down on miles traveled and time on the road. The trucks’ engines operate more efficiently, emitting less pollution, because the vehicles can move more quickly and aren’t constantly stopping and going.

“For every receiver that switched deliveries to the off-hours, we estimated that the total amount of travel saved for the commuters in the city was 10 days,” said Holguín-Veras.

The team found that simply delivering goods overnight, instead of during daytime traffic, reduced a truck’s emissions by an estimated factor of 65 percent.

“Just to give you a sense of the magnitude of the number, President Obama mandated increases in efficiencies for trucks and the goal was increasing energy efficiency by about 25 percent in 10 years,” Holguín-Veras said.

To further examine how changing the behavior of supply chains could reduce energy consumption, a Rensselaer research team—with the support of a $2 million grant awarded by the U.S. Department of Energy in 2017—will soon start collecting data from trucks making deliveries in, around, and between Albany and New York City.

The researchers are interested in examining transport in congested areas as well as long-distance travel, including the use of barges and ships.

The data collection is part of a larger “living lab” project to evaluate and help implement changes in freight demand patterns that will reduce energy use and foster “energy-efficient logistics.”

“The goal is to use a public and private collaborative approach to induce increases in the performance of supply chains—in essence trying to make delivery faster, more efficient, and result in a smaller amount of negative externalities like pollution and congestion,” Holguín-Veras said.

Holguín-Veras and his team believe similar benefits realized by off-hour deliveries can be achieved with other behavior changes, such as consolidation of deliveries and changes in mode.

The researchers are now looking to collect baseline data from companies to help inform possible public and private policy changes. Holguín-Veras said the team is still looking for companies that are interested in participating.