By Dana Yamashita

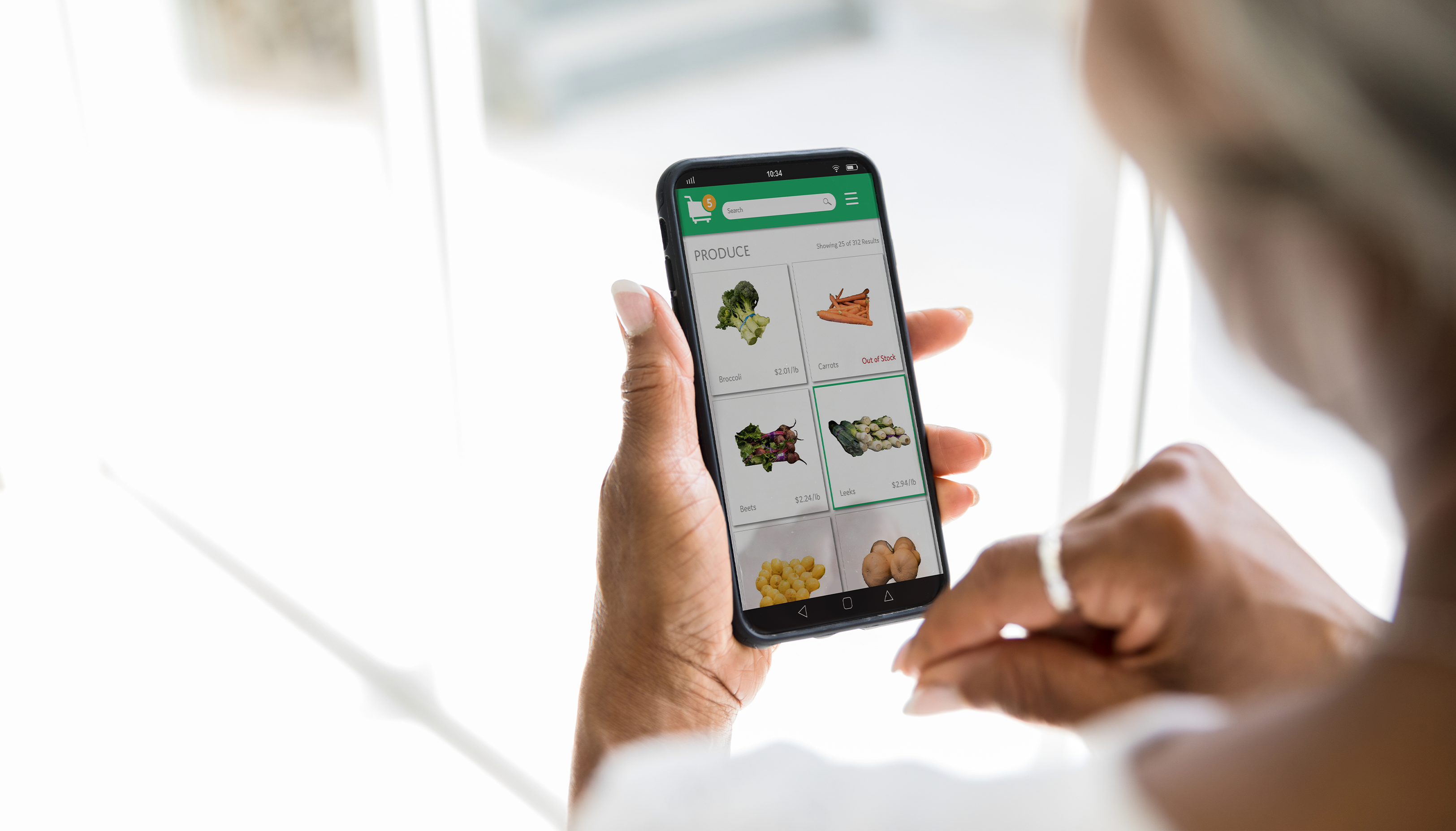

In today’s world, many of us are accustomed to having our needs met relatively quickly — if we want cash, we go to an ATM; we stream movies instead of driving to a theater; we have complete meals delivered to our homes; and there are countless mobile apps covering everything from banking to games. Now, in many places, you can also get your groceries in 15 minutes or less.

Ultrafast grocers are emerging in densely populated cities — a new player in the e-commerce game. They operate out of “dark stores,” or hubs, which are local retail stores that have been converted to fulfillment centers. They typically have a delivery radius of about one mile, allowing their workers to use bicycles and scooters, or even travel by foot, for rapid delivery. But with the good, can come the bad. Ultrafast grocery services encourage people to place smaller and more frequent orders, resulting in more delivery trips. These delivery trips, notwithstanding how they are made, increase traffic congestion and the emissions produced by the traffic stream.

In addition, the advent of ultrafast grocers will bring more trucks to residential areas to restock the hubs, thus worsening traffic congestion and pollution, according to José Holguín-Veras, director of the Center for Infrastructure, Transportation, and the Environment at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. “It’s the price of convenience,” he told The New York Times, “but I feel like I’m going against a tsunami because once you get used to that, why do you want to walk to the local store or plan ahead to buy groceries for the week?”

According to a survey conducted by a team at Rensselaer, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of monthly grocery store trips decreased by 41.6%. Conversely, the number of monthly delivery of groceries increased by 132.2%. The survey was led by Cara Wang, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, and Holguín-Veras.

But what about the toll all these deliveries take on the environment? In another research project, Holguín-Veras collected data from trucks making deliveries in and around New York City to examine the freight demand patterns, with the goal of reducing traffic congestion and pollution. By adjusting deliveries made and accepted to the hours between 7 p.m. and 6 a.m., he found the total amount of travel saved for commuters in the city was 10 days. He also found that a truck’s emissions reduced by an estimated factor of 65% since vehicles were not idling in traffic jams.

While ultrafast grocers are very convenient for people, sometimes the negative consequences of such services are overlooked. The research conducted by Holguín-Veras could help inform policies to combat such effects.