By John Christian, Ph.D., assistant professor of mechanical, aerospace, and nuclear engineering and director of the Sensing, Estimation, and Automation Laboratory

Despite centuries of study, there’s still a lot we don’t know about the Earth. Part of the problem is that, until the beginning of the Space Age in the 1950s, all of our observations of Earth were from sensors on, or very near, the planet’s surface. The utility of space for gaining a better understanding of the natural world was apparent from the beginning, and many of the earliest spacecraft had mission objectives related to Earth or space science.

Understanding more about Earth is critical as we face global challenges like climate change and a growing population’s demand for food, fresh water, and energy. Modern space exploration benefits from understanding Earth in two important ways. First is space-based observation of the Earth itself, which provides measurements used for everything from weather forecasting to commercial agriculture to climate monitoring.

Second, and perhaps less obvious, is the observation of other planets and moons. It may seem strange, but improving our understanding of far-away places where no human has ever been can teach us a lot about Earth. Specifically, we find that one of the best ways to learn about the processes underway on Earth is to observe what is happening elsewhere, an endeavor often called comparative planetology. These other bodies often exhibit certain phenomena more prominently than what we see on Earth, allowing us an opportunity to more easily understand how they work. The study of the atmosphere of Venus, for example, was critical to our current understanding of both the “greenhouse effect” and the devastating effect of CFCs on the ozone in Earth’s atmosphere. Likewise, the study of asteroids and comets allows us to better understand their makeup and distribution, paving the way for technologies that could protect us from possible impacts, if ever needed, or eventual resource mining.

This is where the Sensing, Estimation, and Automation Laboratory (SEAL) at Rensselaer comes in. At SEAL, we’re developing new ways to extract information from sensor data and then use that information to learn about both the natural world and the sensor itself. And, while we look at data from all types of sensors for all types of applications, we’re most interested in images collected by spacecraft.

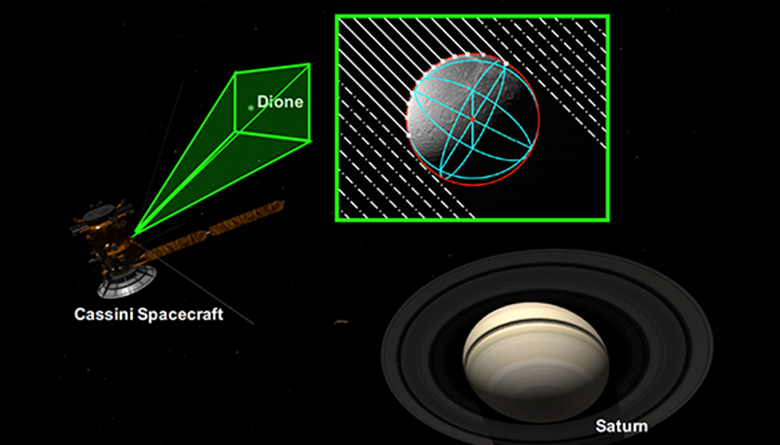

Above, SEAL has created horizon-based optical navigation algorithms that can be used for autonomous spacecraft navigation to determine a spacecraft’s position relative to celestial bodies. This example, generated using Cosmographia, shows the position of the Cassini Spacecraft relative to Saturn and Dione, one of Saturn’s moons (raw image N1592196595, available on NASA Planetary Data System).

One of the things that makes space-based imagery of planets, moons, and asteroids so interesting is how the same data can be simultaneously used for both planetary science and spacecraft operation, usually navigation. As a consequence, the SEAL team has found ourselves at the crossroads of different disciplines that are becoming ever more integrated.

Recently, for example, researchers from SEAL have begun improving methods along the entire image processing pipeline for space science, including image preprocessing, extraction of useful information from imagery, and the fusion of such information into a meaningful science data product for use by planetary scientists around the world. These data products range from high-quality three-dimensional (3D) models to automated counting of surface features (e.g. craters, boulders).

In a parallel effort, the same group of researchers is developing a suite of new techniques and tools that allow a spacecraft to use images for autonomous navigation. The SEAL team has expertise in and has made fundamental contributions to the field of spacecraft optical navigation (OPNAV). Our methods can be used on crewed vehicles, like NASA’s Orion, to help the crew navigate home by themselves if the primary Earth-based navigation system fails. Many of these same methods may be used on robotic spacecraft when visiting distant bodies in our solar system, particularly when there is a need for precision navigation or reduced reliance on Earth-based operators. In this case, processing of space imagery doesn’t produce the science data product directly, but becomes an enabling technology in the infrastructure that allows us to place scientific instruments, such as spectrometers, in hard-to-reach locales throughout our solar system.

The SEAL team at Rensselaer is helping lead the national conversation on the future of space imaging as it relates to both space science and exploration. In June, we hosted a workshop on campus to begin this conversation, and we are looking forward to continuing this discussion at another workshop in the fall of 2019. We believe that space imaging is a critical component to exploring our solar system, with the ultimate goal of improving life for all of us here on Earth.