By Stephanie Loveless, director of The Center for Deep Listening

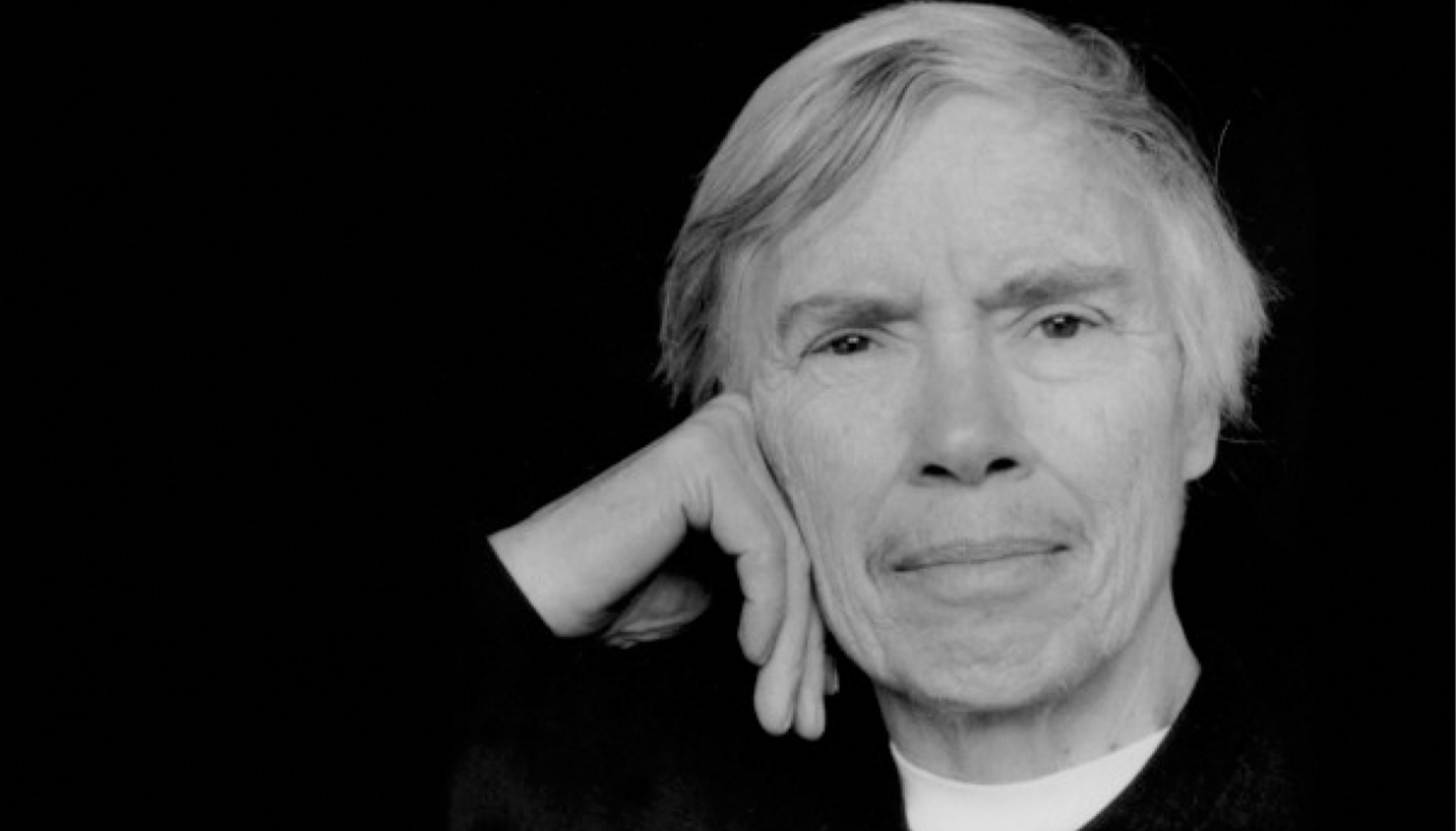

Pauline Oliveros, one of the most important American composers of the 20th century, would have celebrated her 90th birthday this coming May. Oliveros was an early pioneer of electronic music who taught at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute as a Distinguished Professor of Practice for 15 years. Her contributions to music composition, performance, improvisation, and pedagogy were extensions of a philosophy and practice she called Deep Listening, which she described as “listening with your whole body.”

Inherently collaborative, Deep Listening activities were first workshopped by Oliveros in the context of a female-identified collective in the early 1970s. From the 1980s on, Deep Listening workshops, retreats, and the certification program were developed and facilitated in close partnership with author, director, and artist Ione (also Oliveros’ life partner) and movement artist Heloise Gold. Today, the philosophy and practice of Deep Listening continues to evolve through a growing international community of students and teachers, stewarded by The Center for Deep Listening (CDL) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

While Oliveros passed on in 2016, her practices for radical attentiveness to sound continue to be performed, studied, and celebrated worldwide (Deep Listening was, for example, featured prominently in one of Barack Obama’s favorite books of 2020, Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing). Here at Rensselaer, The Center for Deep Listening — founded by Oliveros in 2013 to steward her work — offers experiential online courses in Deep Listening to upward of 100 students from around the world each year, many of whom go on to become certified to teach others.

In honor of this expansive legacy, and in celebration of Oliveros’ 90th birthday, the CDL is launching A Year of Deep Listening — a 365-day exploration of the transformative potential of listening in our current moment through the publication of daily text scores for listening.

What is a text score? It is a is a playful reconception of the idea of a musical score. Traditionally notated scores can only be read by those with specialized musical training, and are generally performed on instruments that require specialized training to play. Text scores are simply notated with words, and are generally performed with modest materials: one’s body, one’s voice, everyday objects, and imagination.

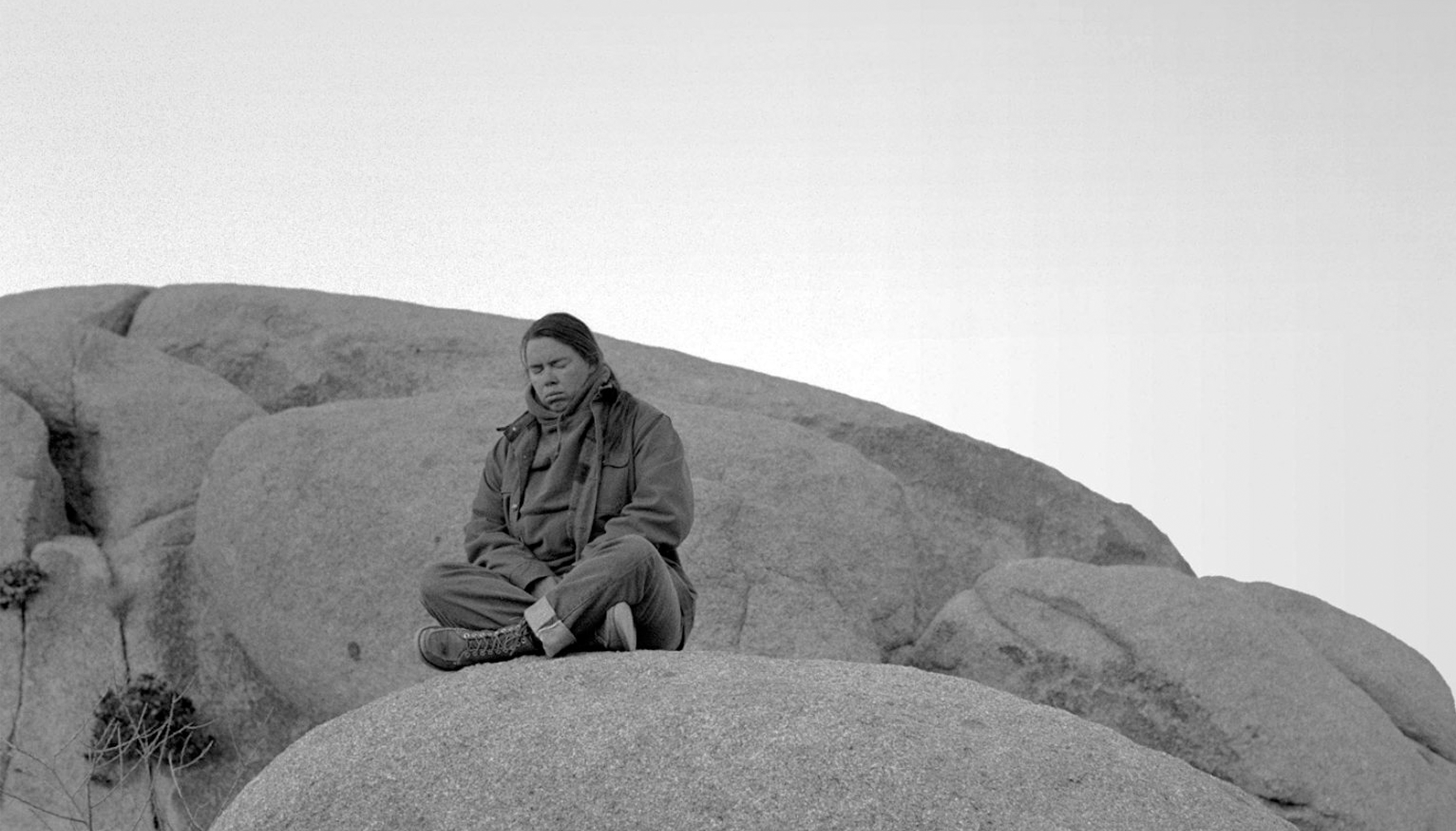

Consider the following Oliveros score from 1971:

Take a walk. Walk so quietly that the bottoms of your feet become ears.

Or “The River Meditation,” from 1976:

By a river or stream, listen for the key tones in the rushing waters. Allow your voice to blend with the sounds that you hear.

While these scores encourage individual attentiveness and receptive collaboration with one’s environment, other scores explore the give and take of interpersonal listening. These scores ask groups to listen for and reinforce each other’s voices, or the sounds of the surrounding environment. In Oliveros’ “Tuning Meditation,” for example, participants are asked to alternate between offering a long tone sung on any vowel sound, and reinforcing someone else’s tone. The piece was performed by 6,000 audience members at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival in 1989, and by over 4,600 participants over a series of online Zoom concerts hosted in 2020 by Music on the Rebound.

For A Year of Deep Listening, the CDL is soliciting text scores that explore the transformational potential of listening in our current moment. What does restorative listening, regenerative listening, or reparative listening sound like? How can we listen for the future we would like to see? The CDL will then publish one such listening score per day — online and across social media platforms — for 365 days, beginning on the date of Pauline Oliveros’ birthday: May 30.

To learn more about Pauline Oliveros and Deep Listening or to submit a text score, visit the Center for Deep Listening website.