By Shekhar Garde, dean of the School of Engineering

I once gave a talk to children at a local middle school about the Molecularium Project. Inspired by Richard Feynman, the main point of my talk was that everything is made of atoms and molecules, and if we understand their interactions, we can understand the physical world. During the Q&A session, the students asked me, “What are molecules made of?” “Atoms,” I said. “But, what are atoms made of?” “Well, protons, neutrons, and electrons.” “And, what are those made of?” On and on, they asked “why,” and I was soon out of my depth.

Why is the sky blue? Why is water wet? Why are things the way they are? It is the chain of “whys,” each one intellectually deeper than the previous one, that was answered by paper-pencil theory or “pure thought” as physicist Steven Weinberg called it, and large-scale experiments, where particles accelerated at high speeds and then collided with each other, spilling their secrets, that led particle physicists to a better understanding of what stuff is made of. That understanding solidified into what is called the Standard Model of Particle Physics.

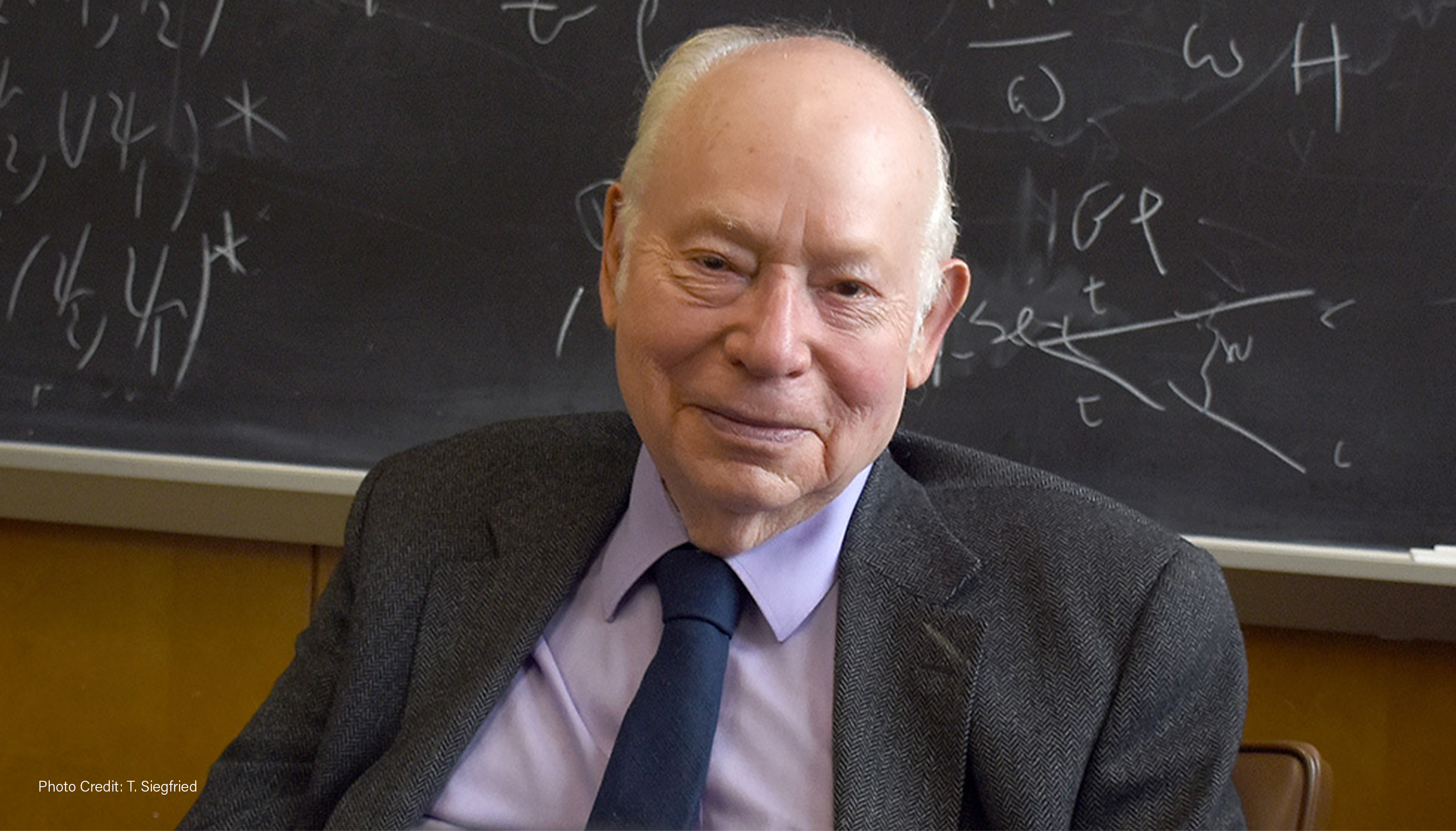

The world became poorer over the summer with the loss of Steven Weinberg, who shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work in theoretical particle physics. Weinberg was a true giant among physicists — a thinker and a humanist. He received an honorary doctorate from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in 2016. We were truly lucky to hear him speak at the annual President’s Commencement Colloquy, a tradition started by Rensselaer President Shirley Ann Jackson, and spend time with him and his wife, Louise Weinberg, a legal scholar.

Weinberg’s advice to Rensselaer graduates was profound. “Scientists, engineers, and architects, in their work, often have an experience that is deeply enlightening, almost ennobling, and is not granted to everyone,” he said. “It is the experience of finding that you have been wrong about something. Not just of being wrong, but of learning conclusively and inescapably that you have been wrong. It’s not that our moral standard is so high compared to other people, it is that rather the analytic ability to do calculations and then carry out observations that allows us to check our ideas as we go along and often learn that they are wrong in a way that we can’t evade.”

He gave an example from his graduate school days, when experiments showed that his ideas about symmetry were wrong. This experience is important and profoundly instructive, he said, for it combats arrogance and opens the mind to new ideas. “When you go forth and get things wrong, as you inevitably will, be willing to recognize that you have been wrong, and even be a little proud that as scientists, architects, or engineers, you have the analytic skills to know that you were wrong.”

In an interview with journalist Bill Moyers, Weinberg once said, “Here we are in this great expanding universe, which does not pay much attention to us, and we are creating an island of life in which there is beauty, scientific research, and love for each other.” We are all extremely lucky to have had Steven Weinberg, one of the brightest stars, among us on our little island of life floating in the vastness of the universe.